Gut Serotonin and the Enteric Nervous System

How the Gut Regulates Mood, Pain, and Digestion

- Published on: 31/Dec/2025

- Posted By: Arka Health

Introduction: Why serotonin is more than a brain chemical

Most people associate serotonin with happiness, calmness, and mental well-being. What is far less known is that nearly 95 percent of the body’s serotonin is produced and used in the gastrointestinal tract, not the brain. This single fact changes how we understand digestion, anxiety, chronic gut pain, and functional bowel disorders.

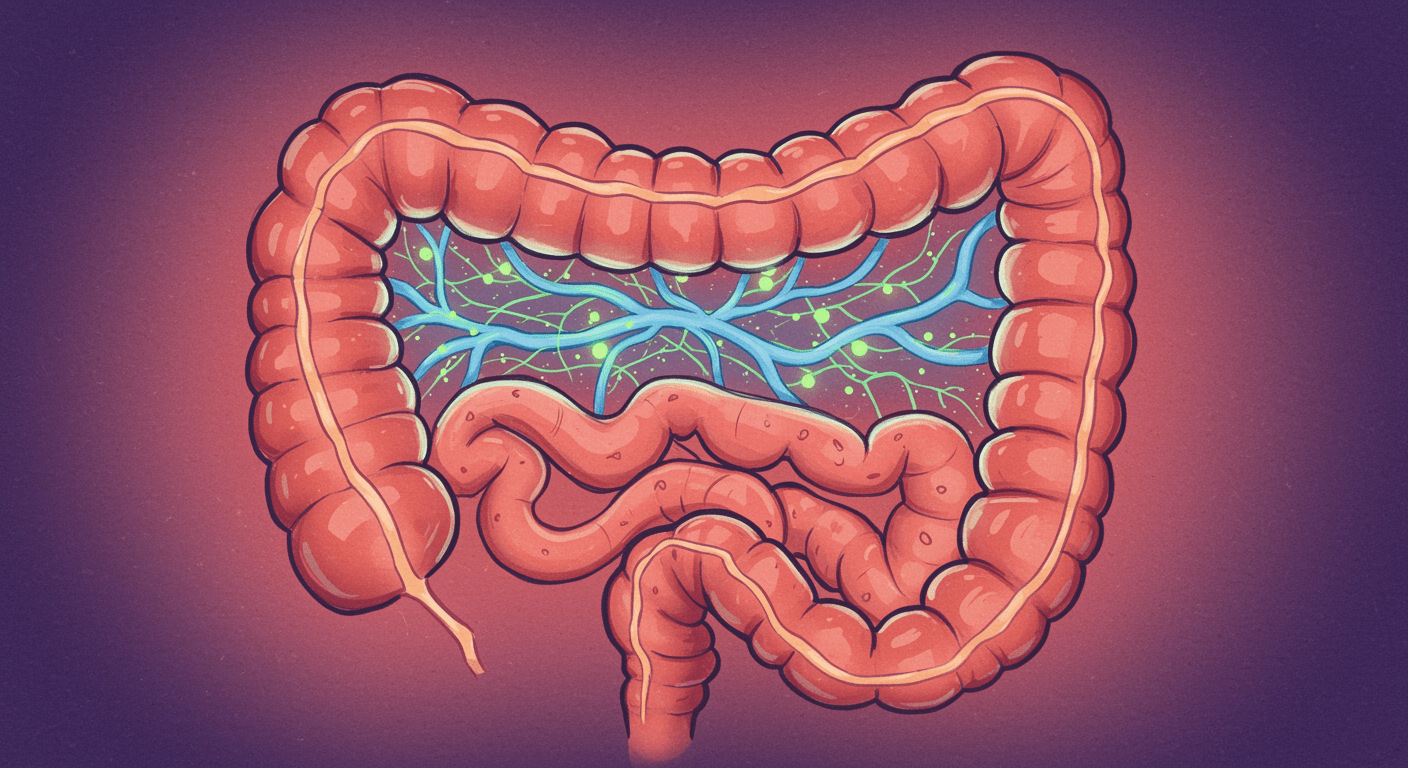

The gut is not just a digestive organ. It contains a dense neural network called the enteric nervous system, capable of sensing, processing, and responding independently of the brain. Serotonin is the primary chemical messenger that allows this system to regulate bowel movement, fluid secretion, pain perception, and communication with the central nervous system.

When gut serotonin signaling becomes dysregulated, patients may experience constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, anxiety, low mood, sleep disturbance, or a combination of all these symptoms. Many individuals are told their tests are normal, yet their quality of life continues to decline. Understanding gut serotonin helps explain why.

This article explores how serotonin is produced in the gut, how it controls digestion and sensation, how it influences mood through the gut-brain axis, and how restoring balance can improve both gastrointestinal and emotional health.

The enteric nervous system: the body’s second brain

The gastrointestinal tract contains its own nervous system with over 100 million neurons embedded in its walls. This system regulates digestion even when communication with the brain is interrupted. Because of its complexity and autonomy, it is often referred to as the second brain.

At the center of this system is serotonin, also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT. In the gut, serotonin does not exist to improve mood directly. Its primary job is to coordinate movement, secretion, and sensation.

Every time food enters the intestine, serotonin signaling helps determine how fast it moves, how much fluid is released, and how strongly the gut senses that movement. When this signaling is balanced, digestion feels effortless. When it is not, symptoms appear.

How serotonin is produced in the gut

Enterochromaffin cells: the gut’s serotonin factories

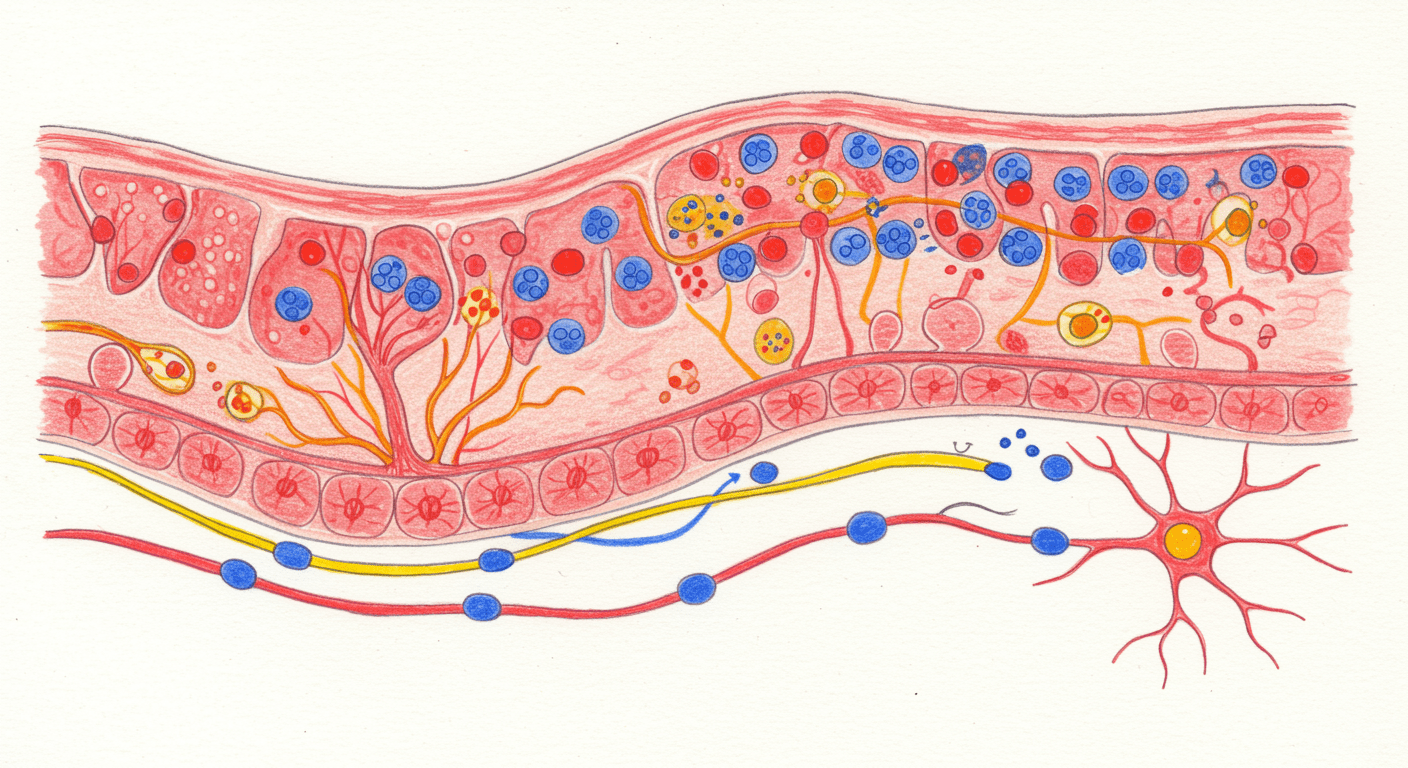

Serotonin in the gut is produced by specialized cells called enterochromaffin cells, which line the intestinal mucosa. These cells act as sensory transducers. They constantly monitor the contents of the gut and respond to physical stretch, chemical composition, and microbial signals.

When food stretches the intestinal wall, mechanosensitive channels on these cells activate and trigger serotonin release. This ensures that gut movement matches the size and composition of a meal.

If these cells become overly sensitive, even small amounts of gas or stool can trigger excessive serotonin release, leading to urgency, cramps, or diarrhea. If they become under-responsive, serotonin release is inadequate and gut movement slows.

Tryptophan and serotonin synthesis

Serotonin synthesis depends on dietary tryptophan, an essential amino acid. In the gut, tryptophan is converted into serotonin through a multi-step enzymatic process that requires vitamin B6, magnesium, and tetrahydrobiopterin as cofactors.

Importantly, gut serotonin and brain serotonin are produced separately. Serotonin itself cannot cross the blood-brain barrier. This means improving gut serotonin does not directly increase brain serotonin, but it strongly influences mood through indirect pathways.

Clearing serotonin signals: the role of the serotonin transporter

After serotonin is released, it must be cleared quickly to prevent overstimulation. This is handled by the serotonin reuptake transporter, commonly called SERT.

SERT removes serotonin from the space between cells and nerves, allowing signals to stop appropriately. When SERT function is reduced, serotonin lingers and continues stimulating receptors.

In many patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS or post-infectious bowel disorders, SERT activity is reduced. The result is ongoing stimulation of motility and pain pathways. In contrast, excessive serotonin clearance may contribute to constipation and sluggish digestion.

This balance between release and clearance is critical.

Serotonin and digestion

Regulating gut movement

Serotonin initiates the peristaltic reflex, the coordinated contraction and relaxation of intestinal muscle that moves food forward. When food stretches the gut wall, serotonin activates sensory neurons that trigger muscle contraction behind the food and relaxation ahead of it.

Low serotonin signaling leads to slow transit, bloating, and constipation. Excessive signaling causes rapid transit, cramping, and diarrhea.

This explains why medications that stimulate serotonin receptors are used in constipation, while medications that block serotonin receptors help reduce diarrhea and pain.

Controlling fluid secretion

Serotonin also stimulates fluid and electrolyte secretion into the gut lumen. This keeps stool soft and allows digestive enzymes to function properly.

During infections or toxin exposure, serotonin release increases dramatically, flushing the gut contents rapidly. This protective mechanism appears clinically as diarrhea. When this response becomes chronic, symptoms persist long after the infection has resolved.

Modulating gut pain

Serotonin affects how strongly the gut senses distension and chemical stimuli. Specialized serotonin receptors on sensory nerves relay signals to the brain via the vagus nerve and spinal pathways.

When these receptors become hypersensitive, normal digestive activity is perceived as pain. This phenomenon, known as visceral hypersensitivity, is central to functional gastrointestinal disorders.

The gut-brain axis: how gut serotonin affects mood

Vagus nerve signaling

Most communication between the gut and brain travels through the vagus nerve. Serotonin released in the gut activates vagal sensory fibers, sending signals to brain regions involved in emotion, stress regulation, and pain processing.

Balanced signaling supports calmness and emotional resilience. Erratic or inflammatory signaling contributes to anxiety, restlessness, and low mood.

The tryptophan diversion pathway

Inflammation in the gut activates enzymes that divert tryptophan away from serotonin production and into the kynurenine pathway. This pathway produces metabolites that are neuroactive and, in some cases, neurotoxic.

As a result, gut inflammation can simultaneously reduce serotonin availability and increase compounds that worsen depression, anxiety, and cognitive symptoms. This mechanism explains the strong overlap between chronic digestive disorders and mood disturbances.

Clinical patterns of serotonin imbalance

Low serotonin tone

This pattern is commonly seen in constipation-predominant bowel disorders.

Symptoms may include infrequent bowel movements, bloating, early satiety, fatigue, poor sleep, low mood, and carbohydrate cravings.

High serotonin tone or hypersensitivity

This pattern is common in diarrhea-predominant IBS and post-infectious states.

Symptoms include urgency, loose stools, cramping, nausea, visceral anxiety, restlessness, and disturbed sleep due to nocturnal bowel activity.

These functional patterns are distinct from serotonin syndrome, which is a rare but serious drug-induced emergency.

What disrupts gut serotonin balance

Microbiome imbalance

Gut bacteria regulate serotonin synthesis and clearance. Reduced microbial diversity, antibiotic exposure, and bacterial overgrowth disrupt this regulation and alter serotonin signaling.

Medications

Certain medications, including antibiotics, NSAIDs, and antidepressants, can alter serotonin dynamics in the gut. While often necessary, their long-term effects on gut signaling must be considered.

Nutrient deficiencies

Inadequate intake or absorption of tryptophan, vitamin B6, magnesium, or iron impairs serotonin synthesis and contributes to functional symptoms.

Environmental stressors

Chronic psychological stress directly increases serotonin release and alters receptor sensitivity, linking emotional stress to digestive symptoms.

Integrative management of gut serotonin imbalance

Restoring balance requires more than symptom suppression. The goal is to normalize signaling, repair the gut environment, and reduce inflammatory drivers.

ARKA Anugraha Hospital approach

At ARKA Anugraha Hospital, gut serotonin imbalance is approached through functional gastroenterology and systems-based care. Evaluation focuses on motility patterns, microbial health, inflammation, nutrient status, and gut-brain signaling rather than isolated symptoms.

Under the guidance of Dr Gaurang Ramesh, care is structured around the 5R framework:

- Removing inflammatory triggers and microbial imbalances

- Replacing digestive factors needed for absorption

- Reinoculating beneficial gut bacteria

- Repairing the intestinal lining

- Rebalancing nervous system signaling

This approach supports long-term regulation of serotonin pathways rather than short-term symptom control.

Conclusion

Serotonin is not merely a mood chemical of the brain. It is a master regulator of digestion, sensation, and gut-brain communication. When gut serotonin signaling becomes imbalanced, symptoms extend far beyond the intestine, affecting mood, sleep, pain perception, and overall well-being.

Understanding this system provides clarity for patients who feel unheard or misunderstood. Functional gut disorders are not imagined. They are rooted in measurable physiology.

Restoring serotonin balance in the gut offers a path toward lasting relief and improved quality of life.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is leaky gut syndrome medically recognised?

Yes. Increased intestinal permeability is well documented in medical research. - Can leaky gut exist without digestive symptoms?

Yes. It may present as fatigue, joint pain, or brain fog. - Does gluten cause leaky gut in everyone?

It increases permeability in all humans, but symptoms depend on repair capacity. - Can stress alone cause leaky gut?

Yes. Chronic stress directly disrupts tight junctions. - How long does gut healing take?

Initial improvement may occur in weeks, full repair takes months. - Are probiotics enough to fix leaky gut?

No. They must be part of a structured protocol. - Can leaky gut lead to autoimmune disease?

It is considered a prerequisite in many autoimmune conditions. - Is food sensitivity testing reliable?

It helps identify immune exposure but should not be used alone. - Does alcohol worsen permeability?

Yes. Alcohol directly damages epithelial cells. - Can children have leaky gut?

Yes, especially after infections or antibiotic exposure. - Is leaky gut reversible?

Yes, with proper intervention and compliance. - Does leaky gut affect mental health?

Yes. Gut-derived inflammation influences brain function. - Can NSAIDs cause leaky gut?

Long-term use significantly increases permeability. - Does healing require lifelong food restriction?

No. Tolerance often improves once the barrier heals. - When should medical supervision be sought?

When symptoms are chronic, multisystemic, or worsening.

Explore Arka Recipes

Discover recipes that blend taste with health, crafted by our experts for your well-being.

Arka Diagnostics

Discover groundbreaking diagnostic services exclusive to India, now available at Arka Health, Bangalore